Molecular Probes: Types and DNA Library Screening Techniques

Molecular Probes: Definition, Types, and Library Screening

A probe is a single-stranded sequence of DNA, RNA, or a specific protein/antibody that is labeled with a detectable marker (radioactive, fluorescent, or chemical tag) and used in molecular biology to detect the presence of a specific, complementary target sequence in a complex mixture.

Types of Probes

Probes are generally classified by their chemical nature and intended target:

- DNA Probes: These are single- or double-stranded DNA sequences used to detect complementary DNA or RNA sequences through hybridization (e.g., in Southern or Northern blotting, or screening DNA libraries). They can be derived from genomic DNA, cDNA (synthesized from mRNA), or made synthetically.

- RNA Probes (Riboprobes): These are single-stranded RNA molecules that are highly specific and often used in Northern blotting or in situ hybridization to detect target RNA sequences.

- Protein/Antibody Probes: Labeled antibodies can be used to probe for specific proteins in techniques like Western blotting or expression library screening. They bind to the target protein based on highly specific antigen-antibody interactions.

- Synthetic Oligonucleotide Probes: Short, chemically synthesized DNA sequences (oligonucleotides) are used when the target sequence is known or partially known, especially for detecting specific mutations or variations.

Screening of Libraries Using Probe-Based Methods

Screening a DNA library (genomic or cDNA) involves identifying the specific clone among thousands that contains the gene of interest. This is commonly done through colony or plaque hybridization, using either direct or indirect probe labeling methods.

Direct Method

In the direct method, the reporter molecule (e.g., a fluorescent dye or radioactive isotope) is physically and covalently attached directly to the probe molecule itself.

Procedure in Library Screening:

- Immobilization: Clones (e.g., bacterial colonies) from a master plate are transferred to a membrane (like nylon or nitrocellulose), creating a replica.

- Lysis and Denaturation: The cells on the membrane are lysed, and the target DNA is denatured into single strands, binding it to the membrane.

- Hybridization: The single-stranded labeled probe is added to the membrane and incubated, allowing it to hybridize (bind) to its complementary target sequence.

- Washing and Detection: Unbound probes are washed away. The location of the bound probe is then detected using an appropriate method (e.g., autoradiography for radioactivity, or fluorescence detection).

- Isolation: The positive clones on the membrane are matched back to the original master plate to isolate the desired clone.

Indirect Method

In the indirect method, the primary probe is not labeled with the final detection agent. Instead, it contains a smaller chemical tag (hapten) like biotin or digoxigenin. A secondary detection molecule, which is labeled (e.g., with an enzyme like horseradish peroxidase (HRP), or a fluorophore) and can bind to the primary tag, is then used for detection.

Procedure in Library Screening (Nucleic Acid Example):

- Immobilization, Lysis, and Hybridization: These steps are the same as the direct method, but an unlabeled or hapten-labeled primary probe is used.

- Primary Detection (if applicable): If the probe has a hapten like biotin, a labeled secondary agent (e.g., streptavidin conjugated to an enzyme or fluorophore) is added, which binds to the hapten on the probe.

- Signal Generation: If an enzyme is used as the label, a substrate is added that the enzyme converts into a detectable signal (e.g., a colored precipitate, light, or fluorescence).

- Washing and Detection: Unbound detection molecules are washed away, and the signal is visualized and matched to the master plate.

Key Advantage of Indirect Method:

The indirect method often provides signal amplification because multiple labeled secondary molecules can bind to each primary probe (or primary antibody, in the case of protein screening), resulting in a stronger signal and increased sensitivity compared to the direct method.

Applications of Recombinant DNA Technology

Recombinant Human Growth Hormone (rhGH) Production

Recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) is produced using recombinant DNA technology by inserting the human growth hormone (hGH) gene into a host organism, most commonly E. coli bacteria. The bacteria are cultured in a process called fermentation, where they produce the protein, which is then isolated and purified to create the rhGH used to treat growth disorders.

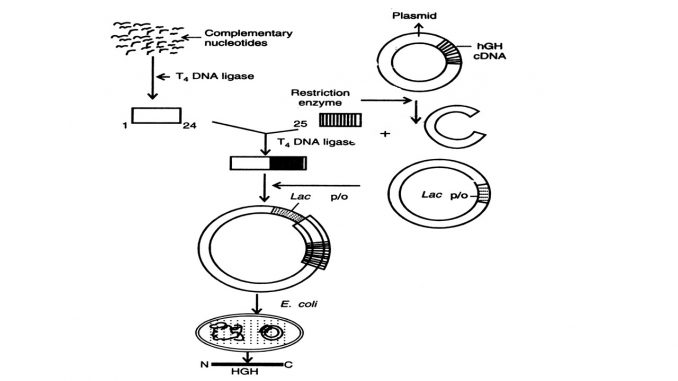

How rhGH is made using recombinant DNA technology

- Gene isolation/synthesis: The gene for human growth hormone is either isolated or synthesized. A common method is to chemically synthesize a gene fragment that codes for the first 24 amino acids and then ligate it with a complementary DNA sequence to create the full gene for expression in a bacterium like E. coli.

- Vector insertion: The hGH gene is inserted into a plasmid, a small, circular piece of DNA, which serves as a vector.

- Transformation: The recombinant plasmid is then introduced into a host cell, such as Escherichia coli.

- Fermentation: The transformed bacteria are cultured in large-scale fermentation tanks. The bacteria multiply and express the gene, leading to the production of large quantities of hGH.

- Purification: The hGH is extracted from the bacteria and then purified through a process of chromatography to ensure its purity and remove any bacterial contaminants.

Why this method is used

- Safety: This method avoids the risk of transmitting human pathogens that could be present in pituitary-derived hGH preparations, making it a safer alternative.

- Abundance: It allows for the safe, large-scale, and consistent production of hGH to meet medical demand.

Medical uses of rhGH

- Growth disorders: rhGH is used to treat children with short stature and growth hormone deficiency.

- Adult growth hormone deficiency: It is also used in adults who have a deficiency of growth hormone.

- Other conditions: Research has also investigated its use in conditions such as Turner syndrome and chronic renal failure.

Bacteriophage

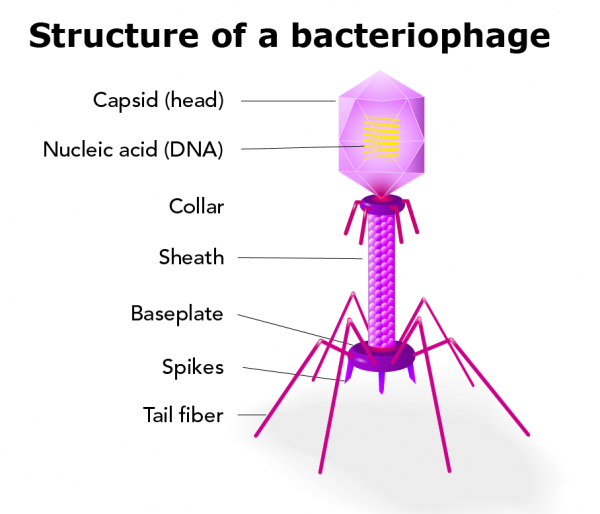

A bacteriophage is any of a group of viruses that infect bacteria. Bacteriophages were discovered independently by Frederick W. Twort in Great Britain (1915) and Félix d’Hérelle in France (1917). D’Hérelle coined the term bacteriophage, meaning “bacteria eater,” to describe the agent’s bacteriocidal ability. Bacteriophages also infect the single-celled prokaryotic organisms known as archaea.

Characteristics of bacteriophages

Thousands of varieties of phages exist, each of which may infect only one type or a few types of bacteria or archaea. Phages are classified in a number of virus families; some examples include Inoviridae, Microviridae, Rudiviridae, and Tectiviridae. Like all viruses, phages are simple organisms that consist of a core of genetic material (nucleic acid) surrounded by a protein capsid. The nucleic acid may be either DNA or RNA and may be double-stranded or single-stranded. There are three basic structural forms of phage: an icosahedral (20-sided) head with a tail, an icosahedral head without a tail, and a filamentous form.

Golden Rice

Golden rice is a genetically modified rice (Oryza sativa) that has been engineered to biosynthesize beta-carotene, a precursor to Vitamin A. Beta-carotene, a pigment responsible for the orange coloration of carrots and other plants, gives the rice its distinctive hue. Although the crop was intended to help combat vitamin A deficiency—particularly in children—in low-income countries that use rice as a staple food, the GMO has been the source of significant controversy.

Vitamin A Deficiency Context

Vitamin A is an essential nutrient for the human body and is only obtained through diet. It is most abundant in fatty fish—especially in fish-liver oils—and is also found in other animal products, including milk fat, eggs, and liver. Although vitamin A is not present in plants, many vegetables and fruits contain beta-carotene or other pigments that the body can convert to vitamin A. In low-income and developing countries, access to these foods can be limited, increasing the risk of a serious deficiency that can cause developmental defects or even death. Vitamin A deficiency is a major public health concern in more than half of all countries, with millions of children affected each year. The World Health Organization estimates that around 250 million people suffer from vitamin A deficiency, including 40 percent of children under five in the developing world. Vitamin A deficiency is the leading cause of childhood blindness, and half of all afflicted children die within a year of losing their eyesight.

Development of Golden Rice

In 1982 German scientist Ingo Potrykus began to research a grain-based solution to the problem of vitamin A deficiency. Given that rice is a staple crop for more than 3 billion people, the cereal grain was a logical and promising candidate. But since beta-carotene does not naturally occur in rice grains, Potrykus faced serious challenges. He began investigating the genetic pathways behind beta-carotene synthesis. About a decade later he was joined by another German scientist, Peter Beyer, and the project was funded in part by the Rockefeller Foundation. The project required more engineering than typical genetic modifications that involve the addition of a single novel gene because the production of beta-carotene is a complex biochemical process regulated by several genes. To generate such a modified grain, scientists leveraged gene editing technology and took the genes responsible for beta-carotene production in daffodils (Narcissus pseudonarcissus) and bacteria (Pantoea ananatis and Escherichia coli) and added these to the DNA of rice. Later versions included genes from corn (maize; Zea mays). Golden rice first successfully expressed beta-carotene in 1999, and the scientists published the results in 2000.

Bt Cotton

What is Bt Cotton?

Bt cotton has been genetically modified by the insertion of one or more genes from a common soil bacterium, Bacillus thuringiensis. These genes encode for the production of insecticidal proteins, and thus, genetically transformed plants produce one or more toxins as they grow. The genes that have been inserted into cotton produce toxins that are limited in activity almost exclusively to caterpillar pests (Lepidoptera). However, other strains of Bacillus thuringiensis have genes that encode for toxins with insecticidal activity on some beetles (Coleoptera) and flies (Diptera). Some of these genes are being used to control pests in other crops, such as corn.

Bt cotton has been genetically modified by the insertion of one or more genes from a common soil bacterium, Bacillus thuringiensis. These genes encode for the production of insecticidal proteins, and thus, genetically transformed plants produce one or more toxins as they grow. The genes that have been inserted into cotton produce toxins that are limited in activity almost exclusively to caterpillar pests (Lepidoptera). However, other strains of Bacillus thuringiensis have genes that encode for toxins with insecticidal activity on some beetles (Coleoptera) and flies (Diptera). Some of these genes are being used to control pests in other crops, such as corn.

Recombinant DNA technology and Bt cotton

- Gene insertion: Specific “cry” genes (e.g., cry1AC and cry2AB) from the Bacillus thuringiensis bacterium are isolated.

- DNA recombination: These genes are inserted into the cotton plant’s DNA, creating a recombinant DNA molecule.

- Transformation: This new DNA is introduced into cotton plant cells using methods like Agrobacterium-mediated transformation or particle gun technology.

- Expression: The modified cotton plant cells then begin to produce Bt proteins, which are toxic to specific insect pests.

How it works in the plant

- Toxin production: The cry genes cause the plant cells to produce an inactive protoxin.

- Insect ingestion: When a susceptible insect larva, such as a cotton bollworm, eats the cotton plant, it ingests the protoxin.

- Activation: The protoxin is activated by the alkaline environment in the insect’s midgut.

- Insect death: The activated toxin forms pores in the gut cell membranes, causing the cells to burst and killing the insect.

Restriction Enzymes

Restriction Enzyme Definition

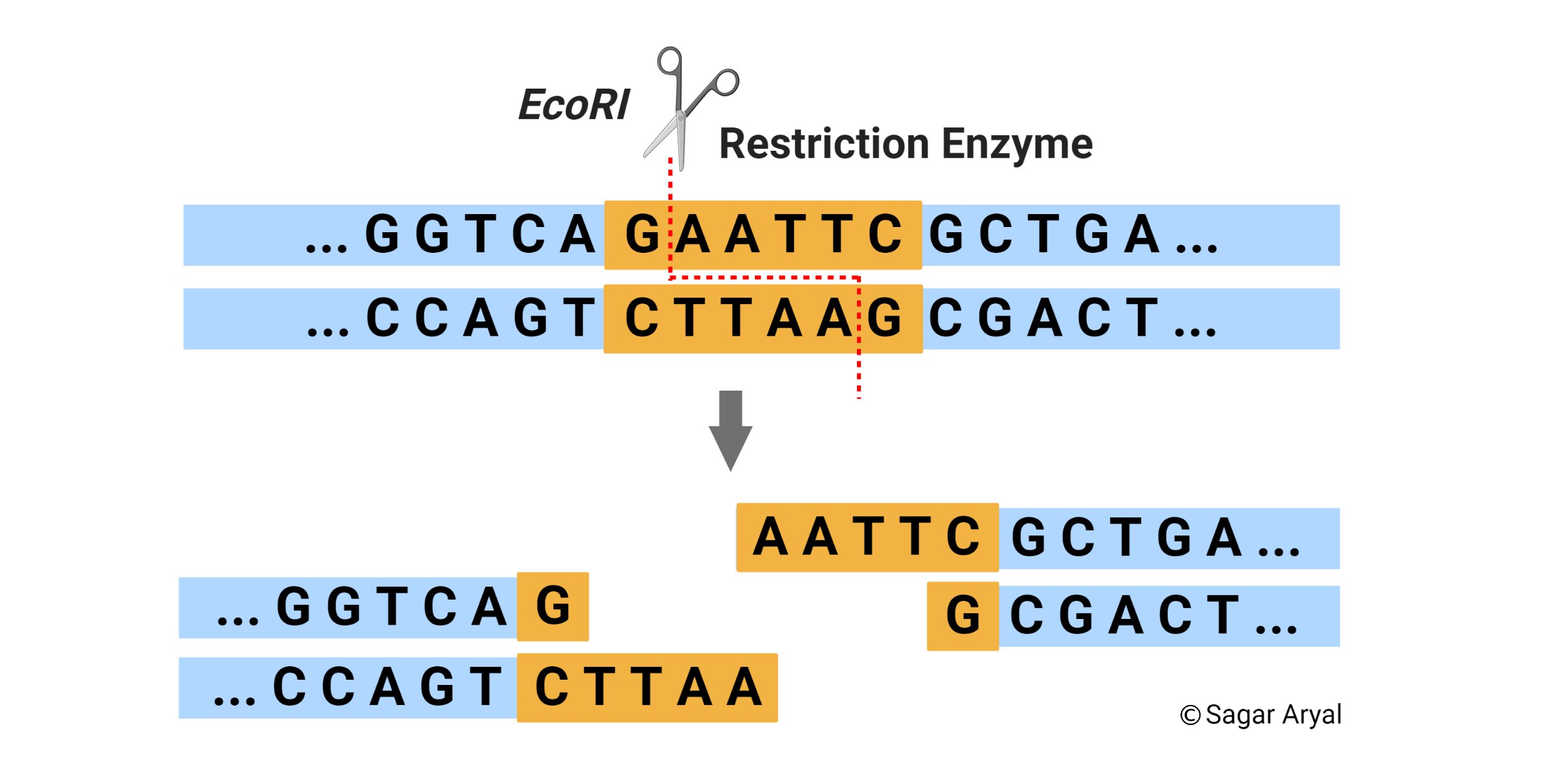

A restriction enzyme, also called restriction endonuclease, is a protein produced by bacteria that cleaves DNA at specific sites along the molecule. Restriction endonucleases cut the DNA double helix in very precise ways. It cleaves DNA into fragments at or near specific recognition sites within the molecule known as restriction sites. They have the capacity to recognize specific base sequences on DNA and then to cut each strand at a given place. Hence, they are also called as ‘molecular scissors’.

Source of Restriction Enzymes

The natural source of restriction endonucleases are bacterial cells. These enzymes are called restriction enzymes because they restrict infection of bacteria by certain viruses (i.e., bacteriophages), by degrading the viral DNA without affecting the bacterial DNA. Thus, their function in the bacterial cell is to destroy foreign DNA that might enter the cell. The restriction enzyme recognizes the foreign DNA and cuts it at several sites along the molecule. Each bacterium has its own unique restriction enzymes and each enzyme recognizes only one type of sequence.

Mechanism of Cleavage of Restriction Enzymes

When a restriction endonuclease recognizes a particular sequence, it snips through the DNA molecule by catalyzing the hydrolysis (splitting of a chemical bond by addition of a water molecule) of the bond between adjacent nucleotides. To cut DNA, all restriction enzymes make two incisions, once through each sugar-phosphate backbone (i.e. each strand) of the DNA double helix.